Navigating the Mental Load with Queer Couples

Madeline Korth, MSSA, LISW-S

September 22, 2025

Many of us were taught If you’re like me, you are hearing about “the mental load” in sessions a lot lately. Seasoned therapists know that whatever is in the zeitgeist will make its way into our work eventually, for better or for worse. But the mental load isn’t just pop psychology – it’s a real thing, and the people carrying it are exhausted.

Several years ago, “You Should Have Asked,” by Emma Clit, a French cartoonist, began making the rounds online.1 The piece articulates the role of women as project managers of their households through a few relatable examples. One notable frame detailing a kitchen disaster ends with a refrain from the male partner that he would have helped, but she “should have asked!”1

It’s tempting to point the finger at men in conversations about the division of household labor. By definition, this problem is highly impacted by how we are socialized in terms of gender. But it’s not exclusive to relationships between men and women. As a couples’ therapist, I have been present for discussions unpacking the mental load with people of many genders, sexualities, and relationship dynamics. Sorry, queer folks: heterosexuality isn’t a quick and easy scapegoat here.

The mental load is not just a byproduct of outdated gender roles or heteronormativity. Whether we subscribe to these ideas or not, we are still impacted by them at a societal, cultural, and interpersonal level. Let’s dig in.

What is the mental load?

The mental load was first defined by sociologist Susan Walzer in a 1996 paper titled “Thinking About The Baby: Gender and divisions of infant care.”5 Her focus was the “thinking, feeling, and interpersonal work” of taking care of new babies.5 In this framework, physical tasks are discrete, whereas mental labor can be abstract or involve multiple steps. Walzer interviewed new mothers and fathers and found that the cognitive processes accompanying early parenthood were predominantly performed by mothers.

Walzer’s work built on earlier sociological inquiries into divisions of household responsibilities – not just parenting. “Housework is not yet allocated a “wage” and is accorded a more negative social reputation because it is assumed to be less useful,” comments one 1993 paper in the journal Sex Roles.2 The same paper argued that the balancing act of domestic and mental labor was overwhelming for women, regardless of whether they worked outside of the home or not, further emphasizing the role of women as household managers.2

Like a lot of social science research in the 20th century, these papers are limited in their scope. Interviewees were only cisgender, heterosexual, married people. While their demographics are not listed explicitly, I have a hunch that many couples were white and middle-class just based on what we know about recruitment strategies back in the day.

In 2025, our understanding of how partnerships, households, and families operate has expanded. These limitations make it hard to both define and discuss the mental load. Let’s look at an example that can affect anyone: making dinner.

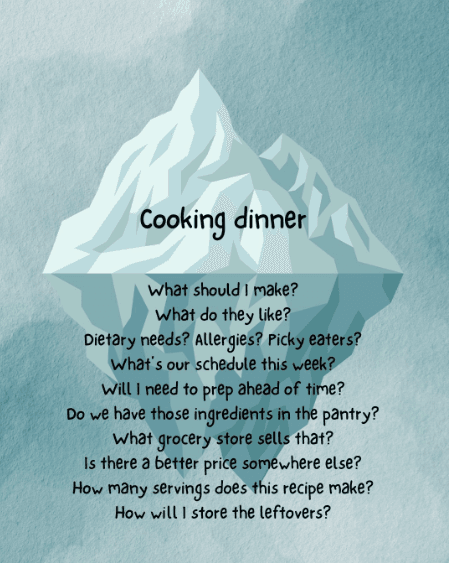

The mental load is like an iceberg. We may be able to plainly see the task at hand with our naked eye, but there is far more labor that lies beneath the surface.

Queer relationships and mental load

The work of unpacking sexuality, gender, and personal identity comes with clarifying our values. This means unlearning some of the harmful assumptions we had internalized. And it can be extra frustrating when we experience the same pitfalls of marriage, parenthood, or cohabitation that we tried so hard to avoid.

When I work with clients who are struggling with unpacking the mental load in their relationship, here is where I start:

1. Figure out where gender socialization may have shaped their strengths or preferences.

“She likes to clean!”

“They care way more about the outside chores than me.”

“He’s the chef of the family for sure!”

Your likes, dislikes, strengths, and weaknesses are all unique to you – and they may differ from your partner! I start by acknowledging that this is an effort made in good faith. Then let’s go a little deeper and think about how these preferences and strengths were formed. In the process of socialization, we are all born without bias, and how we are treated shapes our development.3

Our early experiences, including how others treat us and what opportunities we have access to, are influenced by gender. Even if a client insists they are a better cook than their partner (and very well might be!), that might be due to lack of experience.

From there, we can take a more solution-focused approach. What skills or resources do they need to practice this skill and adopt more of the mental load at meal times? Is it a cookbook? A YouTube tutorial? Some ready-meals from the frozen section?

2. Unpack the erasure that comes with “passing” for some queer people.

The experience of passing as cis or straight comes with mixed emotions. On the one hand, being read as straight or cisgender grants you safety and in some cases, privilege. On the other, it erases your queer identity.

When your client is read as part of a straight couple, they might be subjected to the same stereotypes. For example, your child’s daycare calls Mom first about an incident, even though Dad is listed as the preferred daytime contact. That underlying assumption that women and femmes are the default parent contributes to the mental load.

In therapy, our work is to not only empower clients to speak up, challenge assumptions, and redistribute that load. We also can acknowledge the discomfort that comes with being misunderstood. In situations like the example above, the greater community is contributing to the client’s mental load, but in couples’ therapy, frustration and overwhelm may be directed at her partner.

3. Bring in psychoeducation about human development.

Most of us stop thinking about developmental milestones once we have crossed the threshold between adolescence and adulthood. Nevertheless, it persists, and the stage of life we are in may have a profound impact on our wellbeing.

There is a period of time where adults may be “sandwiched” between caring for the older and younger generations at the same time. If your clients have aging parents and young kids at home, they are in the sandwich years. It’s worth acknowledging how caregiver fatigue can add on to the existing mental load.

Research has shown that women and LGBTQ people are more likely to provide unpaid caregiving for an older family member.4, 5 Cultural beliefs about who are the nurturers and caregivers in our society influences who takes on these roles – and who is prepared to do so. Again, think about who is taught how to be a caregiver. How was that reinforced? And who was not expected to carry out that role?

4. Practice acceptance of the current situation.

Sometimes the division of labor is unavoidable. In particular, if one partner is pregnant, breast- or chest-feeding, there are tasks that their co-parent may not be able to physically do. In this case, your clients might benefit from some radical acceptance.

Yes, this situation is frustrating, but no amount of resistance will change that. They can feel annoyed, angry, burnt out, exhausted, et cetera. There may be no actions that the clients can take to change anything right now. It’s possible to feel how you feel and accept that it isn’t going anywhere.

Acknowledging the imbalance can help ease some of the frustration your clients feel. And like all stages of parenthood, this is temporary. For the time being, what can your partner take off of your plate to reduce the load? Tasks like washing bottles or pump parts can take items off of the mental inventory that accompanies bodyfeeding.

So… what do we do about it?

The mental load is not something we can alleviate with a quick fix. The solution lies at not only the individual level, but also stretches to a societal scale. Whether we subscribe to its ideals or not, we are all living under patriarchy.

We need social, cultural, and institutional changes to create and uphold a more equal society. One such example: policies requiring employers to provide ample time off for working parents. Or shifting the cultural attitude to view men and masculine people as capable caregivers and nurturers.

Therapists play a vital role in this longer-term effort. As clinicians, we have an understanding of other humans at both an individual and societal level. We can use this knowledge to advocate for change politically, and to facilitate perspective-sharing conversations with others who are curious or open-minded. And of course, we can use our skills in the therapy room to rebalance the load one couple at a time.

References

1. Clit, E. (2019, January 6). You should’ve asked. Emma Clit. https://english.emmaclit.com/2017/05/20/you-shouldve-asked/

2. Grana, S. J., Moore, H. A., Wilson, J. K., & Miller, M. (1993). The contexts of housework and the paid labor force: Women's perceptions of the demand levels of their work. Sex roles, 28(5), 295-315.

3. Harro, B., ROUTLEDGE (UK) -- BOOKS, & Adams, M. (2010). Sticks & Stones: Understanding implicit bias, microaggressions, & Stereotypes. In Readings in diversity and social justice. ROUTLEDGE (UK) -- BOOKS. https://www.nea.org/sites/default/files/2021-02/Cycle%20of%20Socialization%20HARRO.pdf

4. LGBTQ+ caregivers: Challenges, policy needs, and opportunities - Center for Health Care Strategies. (2025, May 29). Center for Health Care Strategies. https://www.chcs.org/resource/lgbtq-caregivers-challenges-policy-needs-and-opportunities/

5. Rogin, A., Mufson, C., & Sunkara, S. (2024, March 31). As America’s population ages, women shoulder the burden as primary caregivers. PBS News. https://www.pbs.org/newshour/show/as-americas-population-ages-women-shoulder-the-burden-as-primary-caregivers

6. Walzer, S. (1996). Thinking about the baby: Gender and divisions of infant care. Social problems, 43(2), 219-234.

About the Author

Madeline Korth is a licensed independent social worker with a Master of Science in

Social Administration (MSSA) from Case Western Reserve University. Her clinical work

focuses on LGBTQIA+ individuals, sex therapy, relational work, and the treatment of

anxiety disorders and trauma. In addition to seeing clients in private practice, Maddy

has given presentations on mental health topics throughout Northeast Ohio and

published numerous blogs and articles about mental health, substance use, and

LGBTQIA+ identity.